Beautiful Struggle

Written by Karl Lawrence / Photos by Dondre Green

nightmares in broad daylight with my eyes wide open

only if

this was

just a dream

aunty got cancer screaming she’s dying

all times of the night

difficult to deal with i must admit

living this way

sometimes i get discouraged

in my quiet moments i spend alone

feeling like

nobody really understands my ambition

this radical i got inside of me

but i can't afford to see a psychologist anymore

so i write down

in between the sheets of my diary

all these feelings

i otherwise

would never get the chance to express

sometimes i get discouraged

cuz

sickness

misery

ignorance and death

surround me on all sides when i step outside

yes i’m busy trying to break the cycle

but any time i try to change for the better

it’s my own people that stand in my way

everytime …

only child

watching my own mother deteriorate

squinting her eyes like she’s going blind

on all types of medication

wishing she’d find a way to shake the weight off and maybe come up off those motherfucking

cigarettes cuz lately

we been trading places in hospital beds like it’s a game of musical chairs

plus my father stares at me like he wanna push me off the planet

we exchange hate

sometimes i get discouraged

tired from all the thinking and planning

mapping my way out of this maze

counting down dog days

frustrated frothing at the mouth

from bad breaks and the setbacks common to a young black male

not knowing when it will happen for me

watching all these dumb rappers play monkey for the camera

doing numbers on the billboard

i guess the crackers not interested in your story unless you live in the projects

sell drugs and represent a set

i got to question why is that they don’t want us to be intelligent?

but in the meantime

you could find me

still grinding

on the street selling paperbacks of special k

far away from any media attention

sleeping on a mattress in the basement waiting for my day to come

on the pavement trying to make my way

cuz I got something to say so why should i lie down and be quiet?

i’m no choir boy with his nose in the bible

i’m more of the type to start the fire

write words to spark your mind

feel like my purpose in life is to be like the light from a candle in the dark

or that distant voice telling you that it’ll be alright when you can’t see past your challenges

sometimes i get discouraged but I still get up

stick my chest out to the test and give my best to it

bring my guts to it to get through trying times

trials and tribulations

remember that faith is the bridge over troubled waters when you get discouraged

because i know i do

so i’m just here to remind y'all

that the

struggle itself

is

beautiful

Meet Bronx Anchorwoman: Asha McKenzie

Written by Herbert Norat / Photos by Herbert Norat

The control room is dark and chilly as two producers seated in swivel chairs wearing headsets cordially greet me. I nestle my way onto a chair in a nook behind the producers attempting to become inconspicuous. One of the producers looks up at the behemoth wall clad in multiple television sets of varying sizes and states “Try to stay to your right.” And there she is, anchorwoman Asha McKenzie seated next to her co-anchor Gianna Gelosi, both wearing blood red floral patterned dresses, apparently “clashing” on camera. “Cory Booker announced for president” gasps Asha, as she scans her phone for information. The paradoxical quality in the anchorwoman obtaining headlines from her cell phone while seated in a news studio humorously crosses my mind. The producer chimes in again “Go to your left, thank you.” before playfully bantering with Asha, “Why did they pick you?” referring to my presence at the news station. The jovial camaraderie permeates into the studio and workstations as staffers plan the day’s lunch order. The order of the day? Cheese, in particular, half and quarter pounds of cheese fresh from Arthur Avenue.

The control room

“Doubles” calls out the producer, as Asha laughs alongside weatherman Mike Rizzo who walks on set to prep for his rundown of the weekend deep freeze overtaking the Bronx. The crew prepares to go live coming off a commercial break as one producer counts down “10, 9, 8, 7…” and another producer repositions a camera in the studio using an analog stick. Asha places her cell phone down on the thick glass table in front of her and brushes her hair to one side of her face. “4, 3, 2, 1…” the countdown concludes as Asha brings viewers news of Puppy Bowl 15 on Animal Planet, a Super Bowl pregame show alternative. It’s Super Bowl weekend.

As the early morning segments wrap up, Asha calls me into the studio where I expect to find teams of cameramen and staff running around with gaffs and booms, clear indicators of my newsroom ignorance. But there’s none of that and no one’s there, except for Asha, seated in her anchor chair prepping for the next hour of news. “You can sit over there” Asha instructs me “just watch out for camera six.” Asha’s voice is commanding, full of ethos and she expertly controls her voice’s cadence and pitch as she reads through assorted news items, it’s the sort of voice that’s meant for anchoring. I settle into a directoresque chair and observe the anchorwoman in her natural habitat. All the high tech cameras, monitors and ceiling lights shift and focus on Asha, the center of attention, as she prepares for her next hour of news coverage. Asha scrolls through her cell phone again, reviews the segment scripts on the tablet in front of her, and interfaces with her co-workers “Who’s the producer? Oh, never mind” and “This script is so weird.” Asha has been filming all morning and it’s only 8 am. Asha yawns “Oh my goodness! I need a nap.” Another countdown commences as Asha’s gameface materializes and she looks up at the camera, and live from Soundview in the Bronx, News 12 is transmitted to you.

Asha McKenzie live on air

The news is constantly in flux, ever-changing, ceaseless, and journalists have the responsibility to cover the symbiotic relationships between subjects and consumers as the news balloons into bigger stories or diminishes into mere fillers for a daily news reel. It’s the sort of neverending pace that Asha’s mother, Fay, kept up as a psychiatric nurse and a single mom to six children. Asha, the youngest of the six children, always admired her mother’s work ethic and kindness. “None of us ever became a statistic. She really did her best.” says Asha “She always told me that I had to work even harder to get what I wanted in life.” Asha’s family is a close one, some of them live in the Bronx, and others are based in New Jersey and Philadelphia, but their tight-knit bonds are a testament to Fay’s commitment to her children’s values and growth, no matter the physical distance separating them.

Asha’s resilience and work ethic, molded during her upbringing, carried over into her professional life and helped guide her as she graduated from Montclair University and later became a desk assistant for ABC. Under the mentorship of Michelle Charlesworth and Phil Lipof, Asha learned the ropes by shadowing the reporters two days per week. Asha’s hard work eventually paid off when she accepted a reporting position at WENY News in Elmira, New York, a station where Asha was only one of two minority staff members in the newsroom. This employment situation is not unique as only 22.6% of newsroom staff jobs are held by minority persons, according to the American Society of News Editors. As a black journalist, Asha falls into an even slimmer statistical category as only 12.6% of local TV station jobs are held by women of color. Suffice to say, journalism has a long way to go in diversifying newsrooms.

“You have to be mindful. Everything I say can be looked up.”

Opportunity knocked even louder when Asha was offered a position as a multimedia journalist with News 12 The Bronx. The AP award winning journalist has developed deep connections to her stories and sources in the borough as she fuses her passion for journalism and her commitment to the Bronx. Asha says “I will respond, I don’t ignore work. The borough needs it.”

Asha’s almost finished anchoring as the remote operated camera to my left slightly shifts to the right an inch or so. The minimalist design and phantom operated cameras in the studio have taken the place of newsroom staff that are now only specters here, memories of careers that were once essential, perhaps unimaginable, to run a newsroom without. The future of journalism has seemingly arrived as multimedia journalist positions have become more common at news stations. Multimedia journalists operate their own video cameras and serve as their own photographers, wielding their iPhones for Instagram flash briefs and scrolling through the web for new leads and information. Information, the concept at the crux of journalism, is what Asha is responsible for bringing to Bronxites everyday. And, in the era of fake news and the genesis of Google’s search engine serving as our primary source for information, it is of the utmost importance that our journalists maintain integrity and understand the great responsibility their work bears. “You have to be mindful. Everything I say can be looked up.” says Asha.

“It’s generational, my mom still watches the 5 o’clock news.” Asha smiles, referring to the different ways that people consume news. I tell Asha that I use my landlord’s Optimum subscription to watch News 12’s app on my Apple TV (I know, it sounds difficult, but it’s actually very easy!) Asha laughs and responds “Ahh, so you cheat!” I prepare to ask Asha more questions about automation, social media, and algorithms, and the effects they might have on journalism in the next five years when a congenial producer tiptoes into the studio. “I hate to interrupt but I have a REALLY important question.” whispers the producer “Does anyone want to split a bagel?”

The internet has sped up everything: business, information, journalism, everything. But there are certain interpersonal experiences and fraternity that impossible-looking algorithms and steel equipment can’t produce or convey, like ordering cheese with co-workers, joking in the control room, or simply offering someone a bagel. It’s reassuring to know that our borough’s news is being brought to us by people like Asha, people who care about getting the facts right.

Tribute to the Bronx

Written by Karl Omar Lawrence / Photo by Pedro Pincay

look past the garbage

over the trains and

under the expressway

where they overlook

look through the pollution

in between the crowded avenues and busy streets

there you’ll see

it’s the city

of the bronx new york

the place where I came of age

oh you not familiar?

haven't been past 125th

well if that's the case

come take a trip with me

lemme show you what it's all about

so you could see just how we live

so you could see the blacks and puerto ricans

dominicanos italianos and chicanos

immigrants from many different places in this great melting pot

the strips malls and car washes

liquor stores and pawn shops

children with limited opportunities

not enough options

frustrated in poverty

people pushing bottles and cans in shopping carts to the supermarket

for nickels dimes and quarters

trying to make dollars

junkies and alcoholics strung out

lying face down on the hot concrete

homeless and broken hearted off that

empty

broken

vial needles

syringes

in veins

numb the pain of a fiend who was once fat but now skinny

eyes seen too muchwhat a pitiful sight to see her digging in the trash

arguments and fights outside every night

families beefing with slumlords

for some heat in the winter when it's freezing

hardworking single mamas on ebt running hard not to miss the bus

absentee papas missing in action

where they at?

aunties uncles and cousins under one roof all on top of each other sons

sitting behind prison walls

daughters pregnant before their time

tenement fires so many innocent lives lost

behind the building

knock knock it's a raid

killer coppers chasing robbers killers drug dealers

it seems to be the

only time the news and helicopters come

seldom seen politicians

only come around when it's election time tryna play us like we dumb

racist institutions won't fix our roads or fund our schools

they say we useless

too ghetto

won’t ever amount to much of nothing

so what’s the sense in educating people made to slave in the kitchen

take orders

sweep floors and drive cabs for the rich people on madison avenue?

huh animal habitat picture that

it's like a jungle sometimes

a constant struggle just to get by

summertimes surviving off cold cuts from the corner bodega

wondering if i was gon make it or go under because

i’m up to my neck in it

so don’t push me

close to the edge

trying to clear my headspace and make sense of it all

as I walk down the street and take a look around me

not a bookstore in sight

nowhere to buy groceries of fresh produce but we got the most green space in the whole new york

youth hopeless with no signs that say out

they say we too ghetto

won't ever amount to much of nothing

but what the hell those gringos know about our borough

home of the thoroughbred and the talented

where all this hip-hop got started

before it went pop and lost its spark

we tagged our names in graffiti

so they could see us

because we was invisible

back when power from the streetlights made the place dark

spinning on cardboard at the park jams

stop the violence but ya’ll must’ve forgot about that

when they wrote

us off

left us out and gave us no choice

we made something from nothing

let me tell you a little something about where i’m from

because you don't know nothing!

pelham parkway is where i came of age

so make that a historic landmark

not too far away from arthur avenue and the botanical gardens one of the largest in the world

where roses grow from concrete

bet you aint know that

genius is hidden in the cracks

of despair

if you open your eyes to see

past the garbage

look at the architecture that lines the grand concourse

i’m here to let you know its more to it than Yankee Stadium

in the BX US of A

the place to be if you need a fresh trim from the barbershop call me

where you got to stop at if you want to get your ethnic food authentic

to top it all off like chopped cheese in the Bronx

home to some of the most genuine people you’ll ever meet

guaranteed

we got bright minds

scientists

artists

and if you aint know now you know

the greatest poet of our time is a local!

yeah

I left to get it crackin in DC but you know i had to come back

to be an ambassador

put us back on the map map and give back

to the blocks that gave me my game

made me raise cain and abel to

carve my name in legend and represent

open up shop and buy properties

cuz

honestly we like the last ones left

one of the few places in the empire state

they have yet to gentrify

we can't just lie down and let em take it from us push us out

nah

it’s up to us

to make em put some respect on our name

no obstacle is impossible to overcome

if we come together

stop the bickering and the fighting

stand up to lay claim to the greatness of our city

make our home a better place

if we use our imagination

i have a dream

we can change

Karl Omar Lawrence , 2019 ©

Karl Omar Lawrence is a poet and social entrepreneur from the Bronx, New York. He began writing at the age of 11 years old and has been performing his work ever since he was a teenager. He is a passionate believer in the power that words have to transform people and inspire change in our society. Visit his website at richradical.com for more information on new project releases, music, videos and live performances.

Low Flying Clouds

Written by Tiffany Hernandez / Illustration by Kayla Smith

On a March morning, while the sun was still slowly creeping its way across a nearly-cloudless blue sky, Amina woke up with a jolt, moments before her alarm was set to go off. She went about her morning the way she usually did. Brushed her teeth, shook her half-asleep mother on the couch and started the stovetop coffee maker before anyone else was fully moving. She went through her pile of laundry, looking for a shirt she was almost positive wasn’t actually dirty but she had thrown in the basket for organizational purposes. In their shared bed, Amina’s little brother was still curled up in the tangle of blankets, protecting himself from the frigid cold that encompasses the small room that has two front-facing windows.

Amina always left the house like this, almost-frantic and unsure — taking one last look before she stepped out the door as if when she came back, it might be entirely different. And sometimes, it was. A house once organized and tidy by Amina the night before might transform into a whirlwind of clutter while her mother was in search for one specific item she absolutely needed in that moment. A fridge, filled with just enough food to hold them over for the week, emptied by her little brother who was hungry on a day there was no one to take him to school.

Today, it was the strip of stores around the corner of her apartment that had changed. As Amina was walking out of her apartment building, she noticed a cluster of neighbors holding the front door open, one foot stepping inside the building but bodies turned towards the street, the way a magnet pulls a paper clip irrevocably to its surface.

When something is strange on East 194th street, Amina, as well as most of her neighbors, didn’t flinch. It takes ten minutes of an escalating fight outside her window before she even notices the commotion, even then giving it another few seconds before she popped her head out onto the fire escape to see what was going on. When there was a strange man sleeping in the hallway of her building, she told herself she would wait a few days before mentioning it to her super. Weeks went by and she never did.

So, like any other day, Amina didn’t fully register the oddity of her neighbor’s still and drawn expressions. Until she herself stepped outside the front door, the sky opening up before her.

Mothers stood, arms crossed and feet curled in their slippers and children huddled next to them, hands gripping the arms of their bookbags. The entire bodega staff stood out in the cold without coats on — including the sweet Dominicana, Marisol, who always greeted Amina’s entrance into the bodega with a smile and made her coffee without having to ask her how she wanted. There were barricades, wet concrete and more white people on the corner of East 194th than she had ever seen before at one given time.

“The smell of summer was really the smell of charcoal grills and her father’s carne asada on Fourth of July, her uncles setting fireworks off on the street — little particles of heat hopping through the air. The smell of summer was her boyfriend throwing parties at a house that was not his in Kingsbridge Heights, the smell of burning branches in a garbage can turned fire pit, the smoke trapped in the helix of her curls for days..”

Most of them were firefighters. The rest were news reporters.

As far as she could see, the sky was blue up above but at eye level, the sky was smoke — the color of canvas notebook paper. The kind of notebook paper Amina carried in her bag where she doodled eyes and lips next to the answers to her homework assignment.

The corner laundromat, pizza shop, the beauty salon and grocery store were engulfed. The extent of the damage was indistinguishable. Where the fire started, where it ended - if it ended at all - was lost in the sounds of walkie-talkies, the shuffling of cameras and reporters and in the congestion of residents, both cornered and enthralled in the chaos.

Amina fleed, in the other direction — I still have things to do, I can’t stand here all day, she reassured herself.

The last time there was a fire on her block, only a couple months ago, Amina laid in bed, her brother snoring next to her while the smell of what she could only identify as the smell of summer seeped into her room. The smell of summer was really the smell of charcoal grills and her father’s carne asada on Fourth of July, her uncles setting fireworks off on the street — little particles of heat hopping through the air. The smell of summer was her boyfriend throwing parties at a house that was not his in Kingsbridge Heights, the smell of burning branches in a garbage can turned fire pit, the smoke trapped in the helix of her curls for days and the taste of Corona and purple Doritos scraping against on her tongue.

In actuality, the smell of summer was the fifth floor of the building on the corner of Briggs Ave and East 194th catching fire in the middle of the night last December, Amina would come to find out through social media an hour later. Her breath got caught in her throat. In a moment of both relief and mourning, Amina pulled her brother closer to her body. There was something about fires in the Bronx that sat uneasy in her stomach, a sense of history repeating itself. She felt guilty for being relieved it wasn’t her building, but relieved she was. Amina went to bed that night dreaming of empty buildings with only unharmed children’s toys left behind on the floor, the walls colored black from old fires.

In the months that followed, Amina had almost forgotten about that fire, despite its close proximity. Until this moment, her initial grief had been lost the way most tragedies that just barely touch you do, not out of disregard but by the protective nature of dissociation. Until this moment, Amina was able to evade the feeling that at any moment, a cloud of smoke can take the place of her home.

A honking car summons her out of her foggy memories. She, instinctually, takes a step back from the curb.

All of the streets leading to East 194 were closed off, except Valentine Ave which was the highest point of East 194th Street, each block thereafter gradually lowering down to where East 194 met Webster Avenue. Amina stood at the top of the hill. In front of her, a stream of cars trudged behind one another, one driver after another turning their head to look towards the smoke — wondering for a moment what caused the disruption of their morning commute, a flash of concern before going on their daily routine.

Amina could see her neighbors, still huddled around a barricade of fire trucks and firefighters, watching as places they walk past and visit every day were carved out hollow by both fire and water. It occurred to Amina then that it was only nine in the morning. The laundromat opens at six. She wondered then whose clothes were burned, lost in the midsts of their washing cycle. Her mind flashes to the pile of laundry in the corner of her room. Her brother only had a few clean pair of underwears left.

It wasn’t until that moment that Amina felt the emptiness of her hands, void of her morning coffee. She stuffs her hands into her jacket pockets, turning on her heels forcefully.

Enough, she told herself, I’m not helping anyone by standing here.

But as she ascends up the hill towards the subway station, Amina can’t help but take one last glance over her shoulder at the streets behind her.

A construction worker sticks his head out the window of a new building on the block, a helicopter hovered above in the part of the sky that was blue, untouched by smoke and chaos. The notebook-colored smoke engulfed the corner of E 194th Street and Marion Ave. From here, the smoke just looked like low-flying clouds, quiet and ready to swallow everything whole

New Americans in the Bronx

Written by Herbert Norat / Photos by Herbert Norat

A walk down Westchester Avenue in the South Bronx reminds me of the countless stories that exist in our beautiful borough. The work-worn faces of the food vendors and artisans that line the avenue often belong to immigrants from Mexico, Ecuador, Nigeria, and other Latin American and African countries. Many of these people left their homelands in search of nothing more than a better life for themselves and their children. My mother is one of those “people who left home,” in search of hope and prosperity in the Bronx.

In 1987, my mother, Cynthia, left Nicaragua after a bloody surge in the country’s civil war. President Ronald Reagan's U.S. backed Contra forces had been combating the communist Sandinista government that had toppled the Somoza family's dynastic dictatorship after over forty years in power. This disruption of life and bloodshed propelled my mother to seek out coyotes, people that are paid to sneak immigrants into the United States by way of the U.S.-Mexico border, or, the "frontera." If it sounds ominous, it should. Our country's southern border with Mexico spans over 1,954 miles and its arid and harsh climate is tough on the skin. The possibility of getting lost while crossing is omnipresent for travelers. Then, if you successfully cross into the United States that's where the real “fun” begins. You have to secure passage into a local city, find a way to your final destination, and begin your life in the shadows.

My mother left behind her family, her job at a popular Nicaraguan bank, and her three sons. Juansito was the youngest of her children as he was only 2 years old when my mother left him behind. Everyday I wondered about the internal anguish mom must have felt when she hugged and kissed her baby, turned, and walked out the door towards America.

“We were always vetoed by Mom’s laments over not having ‘Los Papeles’, it was constant and depressing”

After staying in Miami for a few months Mom eventually made her way to the Bronx where she picked up work cleaning houses, babysitting and bartending. Subsequently, my father’s best friend brought him to his favorite pub to flirt with “a new beautiful bartender.” And just like that my parents fell in love and had me. By then her oldest sons and their father had made their way to Los Angeles and had begun American lives of their own. Only Juansito remained in Nicaragua after the civil war had ended. Mom’s quest for her citizenship was a long and arduous one. She had lost thousands of dollars on lawyers and “licenciados” that claimed they could help her, only to be duped. But then something happened that altered our lives forever, Juansito came to the Bronx. My mom secured a visa for Juansito and had his father fly him in. Mom and Juansito had finally been reunited. I spent countless hours teaching Juansito English and in turn he taught me Spanish. We played manhunt on Pelham Parkway with our friends, hopped schoolyard fences to play baseball, and visited all of the iconic New York City landmarks together.

After mom and dad had separated things became harder for us. Not only did we lose the one male figure in our lives who we looked up to, but we also lost the possibility of our parents getting married and providing Mom with “Los Papeles”, or, a green card. It seemed like every time we tried to do something fun or adventurous to escape the confines of our deteriorating home life we were always blocked by Mom’s legal status. By this time Mom was a temporary resident and her fear of being deported seeped into everything we wanted to do, especially travel. We were always vetoed by Mom’s laments over not having “Los Papeles”, it was constant and depressing.

Herb: Mom, can we go see Armando in California?

Mom: No, papa. Remember los papeles.

Juansito: Mom, can we drive to Canada like Berto’s family?

Mom: No, Juansitio. Los papeles.

I often think about my mother’s journey and wonder what life outside of New York City would have been like for our family. But, it’s the Bronx’s grit and toughness that allowed us to learn how to survive and become good honest men in the face of adversity. But, in Trump’s America a sense of fear and anxiety has overtaken our political discourse and permeates everyday life. Families visiting parks, schools, and libraries are afraid of Trump, ICE and the possibility of apprehension and deportation. It’s a scary time to be an undocumented immigrant in America. The same fruit vendors and artisans that are threatened by the government are our neighbors that are simply trying to make a livelihood to support the Juansitos of the world.

This is how Mom lived most of her adult life in the Bronx. In the shadows, afraid of opportunity and advancement, and constantly in fear of the government finding out she didn’t have “Los Papeles.”

Not Without A Fight

Written by Samantha Blake / Photos by Dondre Green

When gentrification made an unwelcome visit to Jessica Martinez’s Bronx neighborhood, it arrived suited-up and clothed in camouflaged gear. She had spent her whole life calling Dyckman, Washington Heights and the South Bronx her home, so when changes swooped into her uptown New York community, Jessica recalls immediately feeling a difference in the vibe, before actually seeing the difference with her own eyes.

“In the park we would get weird looks, which hadn’t happened before,” she recalls. Suddenly the routine of hanging out with her friends in public felt wrong. “We were going to our regular bar and we just got upset. The crowd started changing. We felt like the place itself started catering to a new crowd.” Soon enough, the subtle changes became more apparent. “Walking the streets uptown now, it’s like a ghost town. All the stores that my friends and I knew growing up, they’re mostly gone,” she says, recalling all the mom and pop shops that have now been replaced. “I was in Mott Haven and I was in shock, like ‘Where am I?’”

In recent years, the Bronx’s Mott Haven community experienced a facelift, with a slew of new businesses. Yet even with the transformation, she argues, “right across the bridge is the projects and you see the disparity.” It was that visible disparity that prompted protests in a few uptown communities, including Inwood’s Sherman Plaza. “They wanted to turn Sherman Plaza into a shopping center of sorts. They wanted to make it bigger... right across the street from the park,” she recalls back in 2016. That’s when the community became furious and residents began protesting.

Fueled out of anger and inspired by the protests, Jessica gave birth to what is now called Save Uptown; a project under her gnrtn.WHY (Generation Why) brand, committed to putting up a fight against uptown gentrification. Save Uptown is the message branded across the apparel Jessica sells, which includes hoodies, sweatshirts, crop tops, t-shirts and tote bags, sold at www.gnrtnWHY.com. A percentage of the sales are used to create care packages and lunches for the homeless. The movement that started off with stickers plastered across the neighborhood, has now expanded in the past year to a growing brand with huge support. Bronx-bred comedian, Mero of Vice TV’s Desus and Mero, has even sported the brand on his television show.

Still, even with all the love, the brand has faced hate from naysayers. “Save Uptown? You’re a little too late for that,” they’ve told her.

Many don’t quite understand why the brand does not support neighborhood change. Jessica argues, however, “we are not against change. We are against the displacement of people and the expulsion of culture.”

“People focus on the wrong thing. We’re not talking about what really matters. I get angry at what’s happening, but also angry with the misinformation that’s out there. I think a lot of people focus on the racial aspect of gentrification and when you ask someone what they think about gentrification, the first thing they say is ‘white people.’ My thing is, yes, that is definitely a side effect of gentrification, but it’s not gentrification. We should be talking more about the people that are getting displaced. Where are they going? What’s happening to them? What are they going through? Why are we so focused on coffee shops and dog walking?”

She adds that although gentrification might be bigger than herself, the goal of the brand is to start a conversation and spread resistance. “I know I can’t take on this whole societal structure. I know that me, one person, I’m not going to go against that [on my own]. My goal is to get my peers involved, even if it is through conversation.”

“We are not against change. We are against the displacement of people and the expulsion of culture.”

“A lot of people don’t like what I’m doing,” she continues. “They tell me a sticker is not going to stop gentrification and people feel like maybe I’m further racially dividing the neighborhood, because they look at this as an attack on the gentrifiers. But it’s like, are you so privileged that you feel like even this struggle is about you? I’m not doing this to attack you. I’m doing this to bring awareness to my people, to the people that are being affected by this and don’t even know why.”

Though her brand mostly appeals to young people, the gnrtn.WHY founder also worries over the elders in her uptown neighborhood. When she’s not busy with her brand, Jessica serves her local church, where she says the elderly often go to seek help. “They’re scared. It’s an immigrant community so they see a paper from the city and they get scared. They don’t know what to do.”

In the past two years, she’s observed that gentrification coupled with the English-to-Spanish language barrier has been very crippling. “I started going to the rezoning meetings to try to figure out what was really going on and in those meetings, I would notice that they really make it difficult for [attendees]. They get small rooms so that a lot of people cannot fit. They barely get interpreters even though they are in a predominantly Hispanic community.” Jessica says the interpreters are not Hispanic and for whatever reason, they always have to leave the meetings early. “Things like that make it difficult for the community to get informed.”

“There weren’t a lot of people of color in those meetings. Our people need to do better at getting informed and really putting priority on things.”

She’s willing to admit, however, that the failure she sees at the rezoning meetings don’t completely fall on the city’s shoulders. “There weren’t a lot of people of color in those meetings. Our people need to do better at getting informed and really putting priority on things.” Jessica hopes that her brand will help bring more awareness to her people and take away the culture of fear.

And to the people who say gentrification is good for the Bronx’s economy, Jessica argues that, “Yes, gentrification can be good, but it’s usually for a certain crowd. Yes, they might have new services available in the neighborhood, but it’s usually not even available to the people who have been [living] there. Yes, our streets can get cleaner and things can look nicer but I don’t feel like that’s ok if it comes at the cost of a whole community. Yes, there are good side effects of gentrification, but I don’t think that we reap them. I don’t think that we ever get to see that side, unless it’s [neighborhood] beautification, but I don’t need that. I want my community to be what it is. So if we’re all being wiped out so things can look nicer, I don’t think that’s good.”

Though the activism behind her brand is often fueled by anger, Jessica also receives a lot of positivity. “I get so much love, that it’s overwhelming,” she says. “People are writing to me, and then they find out that I’m a girl and that I’m young and they’re like ‘wow that’s insane.’ I have a lot of love and support from people who think it’s really cool that I’m young and that I’m interested...but really, I’m here to learn. I’m not here stating that I know everything about gentrification. I’m learning along with [the community].”

Jessica also gets messages from past residents who by now, have moved out of New York. “I grew up in the Heights...I visited and it’s completely different,” some of the messages say. “What you’re doing is amazing. Thank you so much.” The community love and support is what inspires Jessica to keep fighting for her ‘hood.

You can follow the Save Uptown movement on Instagram @gnrtn.WHY or at www.gnrtnWHY.com

Bronx Sidewalks Need a Cleanup

Written by Samantha Blake / Photos by Dondre Green

Take a walk down Bronx Boulevard and you’re sure to be greeted by food wrappers, used toothpicks and most notoriously, dog feces. In fact, at the Montefiore Medical facilities between East 234th and East 236th street, lab tests placed in outside pickup bins, sit just a few feet from piles of dog waste.

There are very few public litter baskets in this North Bronx community, so pedestrians tend to throw personal garbage right on the sidewalk. Although residents have the right to request public litter baskets, a September request for a litter basket was denied by the Department of Sanitation (DSNY). “It’s a low trafficked area and placing a litter basket there would attract further dumping,” James O’Connor, a Community Associate at DSNY informed Bronx Narratives.

However, with the presence of a cardiovascular facility, an OB/GYN and Geriatrics center, along with the Metro North Railroad Woodlawn Station just two blocks away, many would argue that the area receives a moderate amount of traffic – enough traffic to deserve a garbage bin.

“[The Department of Sanitation] should come clean the sidewalk, but they don’t.”

Although street cleaning happens here six days a week, sidewalks are not included in that process. Business owners and employees on that street gave cleanliness a poor rating. Pedestrians have also spotted rats in the daytime. “[The Department of Sanitation] should come clean the sidewalk, but they don’t,” says Tanairy Gonzalez, a medical secretary at the OBGYN facility on the block.

And that’s where finger pointing and the blame-game come to play.

Tamar, a Customer Service Representative at NYC’s 311, says the DSNY is not responsible for sidewalk cleaning. They are only held responsible for garbage removal, street cleaning and snow removal. “Residential property owners must clean the sidewalks adjoining their property and 18 inches from the curb into the street.”

As for the neighborhood’s animal waste problem, there are no “Curb Your Dog” signs to remind dog walkers of their responsibility. In fact, since 2013, there has been a cutback on more than 1,000 dog waste signs, in an attempt to clear up sign clutter across NYC. At the time, former DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan told the New York Post that, “New Yorkers know they need to clean up after their dogs, so I don’t foresee any problems....” Four years later and residents feel dog waste continues to be an ongoing issue.

Employees in the neighborhood also agree they have witnessed the DSNY police hand out more fines for parking violations than for dog waste.

According to the city’s Pooper Scooper Law, property owners are expected to clean up animal waste, even if the animal doesn’t belong to them. So when a dog litters on your sidewalk, if the dog walker doesn’t clean up, that waste becomes your responsibility. However, property owners do have the right to report any dog walkers who fail to pick up after their dogs. Property owners can call 311 or file a Dog or Animal Waste Complaint online. Violators are subject to a $250 fine. This law does not apply to Service Dogs being walked by those who have special needs.

Since Bronx Narratives began researching this story in late September, sidewalks have become visibly cleaner, proving that, neighborhood cleanliness is not just one party's responsibility. When the DSNY, property owners and pedestrians each do their part to pick up trash and properly dispose of litter, residents experience a cleaner, more improved Bronx.

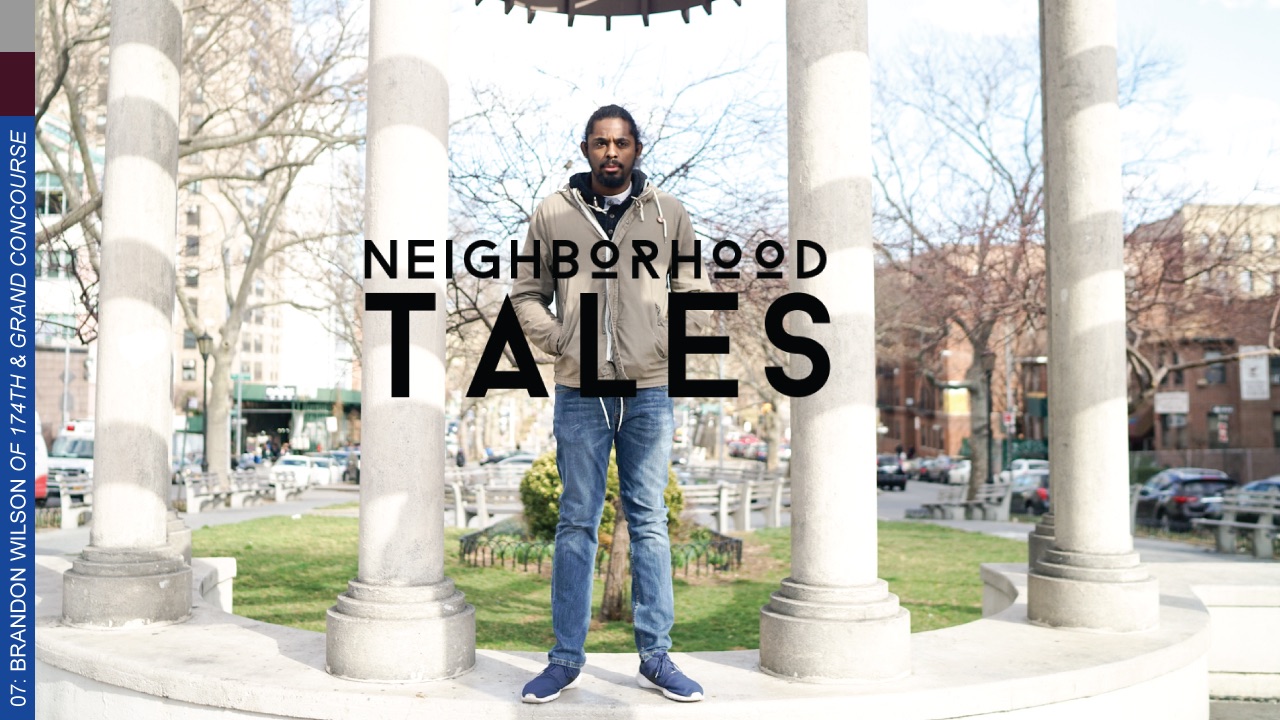

Neighborhood Tales (Episode 07): Brandon Wilson

Q+A by Dondre Green / Video by Kevin De Los Santos

Our seventh episode of Neighborhood Tales, featuring Grand Concourse resident, Brandon Wilson.

Neighborhood Tales: A new editorial series that'll highlight the diversity of Bronx neighborhoods and help provide a visual identity, with stories told by the people who live there.

Neighborhood Tales (Episode 06): Alex Bondarev

Q+A by Dondre Green / Video by Kevin De Los Santos

We're happy to resume content with a new episode of Neighborhood Tales, featuring Pelham Bay resident, Alex Bondarev.

Neighborhood Tales: A new editorial series that'll highlight the diversity of Bronx neighborhoods and help provide a visual identity, with stories told by the people who live there.

Neighborhood Tales (Episode 05): Holly Leicht

Q+A by Dondre Green / Video by Kevin De Los Santos

We return with a new season of Neighborhood Tales featuring Spuyten Duyvil resident, Holly Leicht.

Neighborhood Tales: A new editorial series that'll highlight the diversity of Bronx neighborhoods and help provide a visual identity, with stories told by the people who live there.