How Do You End Hate?

Written by Javon Chasten / Photo by Oliver Ragfelt

In the 50’s and 60’s we had segregation, and Jim crow as the preeminent figures so to speak of racism. We had something tangible to focus our energy and efforts towards putting an end to. We could mobilize and target specific locations that openly embodied these ideologies and practices. We were able to aim our acts of civil disobedience at the right places to leave the strongest message.

Today segregation has ended, or at least the blatant signs on the front door. However what fueled these practices has far from been abolished, demolished, or destroyed. So I begin to ask myself, how do you end hate? How do you destroy a feeling? How do you abolish an emotion? An emotion, feeling, thought, solely directed at anyone with a darker hue than those with fair skin and those with anything but historically European features.

The simple answer logically seems to be love right? Both hate and love take the same amount of energy and effort to truly do. And when I say truly do, I mean putting your ALL into these things. Focusing the maximum amount of energy and effort to sustain and maintain these beliefs and practices. Yet I find myself faced with a new question, I don’t know why you hate us, and quite frankly I don’t know why we should love you?

My people and my ancestors have done nothing to you historically, by way of account through your own text books and teachings. None of my people came up to the captains of slave ships looking to hitch a ride here. This has all been by the design of YOUR forefathers, and perpetuated by your Grandfathers. When the Constitution was written we were only considered to be three-fifths of a person, so the term “People” in that same Constitution didn’t, and has rarely, represented us since the dawn of this country.

I say all that to again ask the question, why do you hate us, and why should we love you? And when I say you, you know who you are. This isn’t some written condemnation on white people, this is my written condemnation of racism and senseless hate. You can’t fix what is broken. You can’t replace pieces that you didn’t know were there to begin with. Racism is a broken concept, it can’t be replaced with Love when you don’t know where the hate truly comes from.

I don’t know if you want us to love you, I don’t know if you will ever love us, what I do know is that WE outnumber YOU. Those old systems you built on hate are being broken. Those old motions of violence are being exposed. Those old ways of thinking are being changed and it's time for you to change with it. The world as you once knew it of us standing still and just taking orders is over. You aren't a master anymore.

This country, and more importantly this world, are no longer your plantation that you can beat, sculpt, groom, or cultivate in a way you deem fit. The power is slowly but surely shifting to the people. We are at a tipping point in history, a place we’ve been many times before, and will likely be time and time again. So long as we continue to put pressure on the needle, the needle will shift; slowly but steadily. One day we'll look back and realize the needle is much further than it was when we began pushing, unfortunately that day is not today.

With all the progress we’ve made in science and technology, it’s such a shame we’ve made so little progress in humanity and empathy. How long will we allow classifications to keep us apart?

Javon Chasten is an artist and writer born and raised in the Bronx.

To see more work and get updates follow him on Instagram and Twitter .

Hands Up!

Written by Javon Chasten / Photo by Clay Banks

What is a protest? According to Google a protest is “a statement or action expressing disapproval of or objection to something”. A protest can be made in so many ways; kneeling, sit ins, bus boycotts, posts and tweets, marching. All powerful statements that send a message or spark a conversation. However what makes a protest, or who rather, are the people!

Red, Black, and Green. Those were the colors chosen by Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. for the Pan African flag. A flag that has become a common sight in the streets across the United States of America. States that seem far less united recently than the country’s name would suggest. One of Garvey’s plans and dreams was to facilitate African American migration to Liberia. Almost 80 years after his death, and African Americans, and all people of color, are fighting for our liberation here on American soil. Today thousands of modern day freedom fighters and revolutionaries have flocked to the streets of the United States, and streets around the globe, to demand the freedom and right for Black people everywhere to live without the fear that our skin color will make us targets. That it will no longer be open season for us as if we are doe’s and buck’s in a forest.

Signs in the windows of stores, homes, and apartments reading “Black Lives Matter” can be seen all around. Workers standing outside of storefronts cheer on those marching. Tenants hang outside their apartment windows banging pots and pans to show their support of protesters. In the sea of those marching are people of all colors, ages, occupations, and backgrounds. A beautiful sight of togetherness and camaraderie. Good samaritans hand out water, snacks, and food. Everything from peanuts to vegan empanadas were given to protesters who were tired and covered in sweat from the glaring sun above. At one point the heavens seemed to part, granting those marching a refreshing shower for a few moments. Rain would not deter anyone from marching to get their messages across, that the systematic racism of old will no longer be tolerated and blindly accepted.

Thousands of hands raised in solidarity to signify the many Black and brown unarmed men, women, and children who have died in front of the guns of trigger happy police officers. Names like Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Alton Sterling, Breonna Taylor and Philando Castile can be seen written on signs raised all around you. The name of George Floyd is shouted through the streets in unison. His is just one of many names on a sad, yet long, list of people who died at the hands of police brutality. A brutality that is all too common for Black and brown people. Historically police rarely receive any type of real punishment for their acts of violence. It seems like they are held to lower standards than that of the average American citizen.

There is no comprehensive government data on the topic, but most, if not all, independent studies show that Black people are killed at a disproportionately higher rate than that of any other race of people in America. Mappingpoliceviolence.org, which uses data from 3 databases - Killed by Police and Fatal Encounters, and the U.S. Police Shootings Database, says that 99% of police killings from 2013-2019 went without a conviction. The site also states that in 2019 police killed 1,098 people in America. Of those 1,098 people, Black people killed account for 24% of those deaths, despite only being 13% of the American population.

Many of these deaths came from false raced-based 911 calls. An old trend that has gained new attention thanks to the advancement of technology in the form of camera phones. By now I’m sure we’ve all seen at least one video of an outraged white woman threatening to call the police on Black people for seemingly no reason. Some of which are quite hilarious, but its origins are sinister and heinous. The story of Emmett Till comes to mind. A young 14 year old boy who was falsely accused of flirting with or whistling at a white woman in a grocery store. Till was kidnapped, beaten, mutilated, and murdered. His body was thrown in the Tallahatchie River, and left there for three days before it was discovered. Today we’ve seen Black people threatened with calls to the police because they were barbecuing with family in a park, walking into their apartments, or like Ahmaud Arbery, jogging in a neighborhood. Being Black should not be suspicious and make someone a target.

The persistence of the people has begun to pay off though and progress has been made. One of the focuses of the New York marches was to repeal 50-a, which was a state law that did not allow the review of personnel records of police officers, firefighters, and corrections officers. Therefore not allowing police misconduct records to be seen by the public. On June 12th however New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation into law that repealed 50-a, bans police chokeholds, and prohibits false race-based 911 calls.

That has not stopped the call for continued progress and reform. The marches have not, and will not stop there. As long as police brutality goes uncharged and unpunished, the people will not and should not let up. So long as unjust laws remain written, we must fight to rewrite them. Change is the only constant, and the time for change in our system is now!

Javon Chasten is an artist and writer born and raised in the Bronx.

To see more work and get updates follow him on Instagram and Twitter .

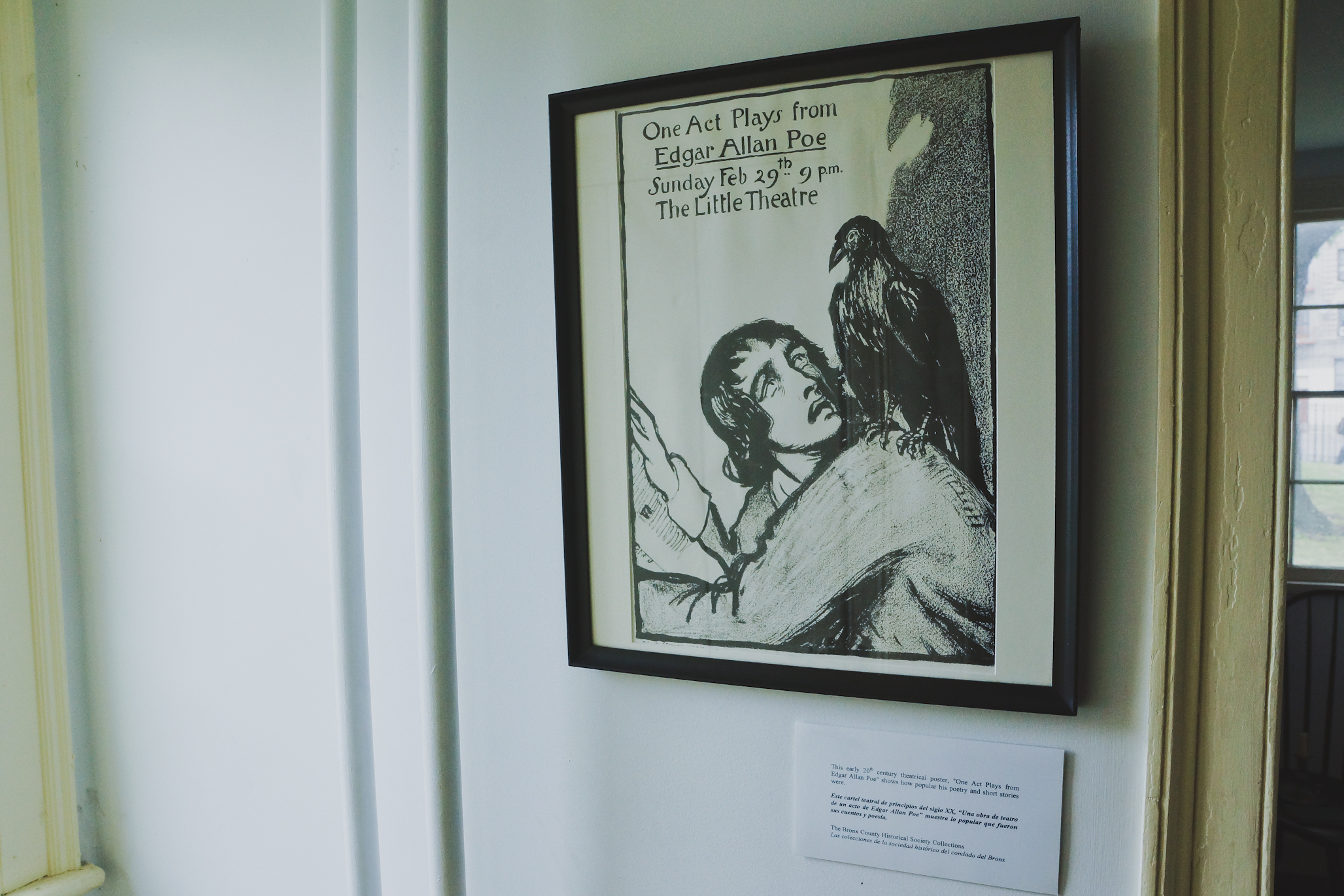

Poe in the Bronx

Written by Herbert Norat / Photo by NYPL Digital Collections

Edgar Allan Poe was one of the Nineteenth Century’s most intriguing writers, an investigative journalist, and, for a brief period of time, he was a Bronxite. The brilliant gothic poet once lived in the very same borough where the New York Yankees play baseball and Arthur Avenue arguably produces the finest Italian cuisine in the country. And, while Poe lived in the Bronx he created some of his finest work, including “The Bells”, “Eureka”, “The Cask of Amontillado”, and “Annabel Lee”.

“Poe would walk the full length of Highbridge in solitude and cross down into Manhattan for the thrill of the city that never sleeps. One can only speculate about the poems, prose, and verse that took shape in Poe’s mind during these therapeutic strolls.”

In 1846, the Bronx was rural and home to farmers such as John Valentine, who rented out his cottage to Poe, and had slowly developed since the early frontier days of founding Bronx farmer Jonas Bronck in the 1600s. The lush pastures, abundant trees, and proximity to Manhattan made the Bronx an ideal place to run a farm and raise a family. In later years, prominent Bronxites, such as New York Times editor Abe Rosenthal, would reflect on their parents’ insistence to enjoy the Bronx’s bountiful nature. In Arlene Alda’s Just Kids from the Bronx, Rosenthal recalls his mother’s instructions ‘“Fresh air!’ she would announce. And then from her lips came the command that rang through every apartment in the Bronx neighborhood every day: ‘Go grab some fresh air! Out! Fresh air!’”

One might assume that Poe distanced himself from contemporary society to wrangle the masterpieces swirling around his head. But it was Poe’s wife, Virginia Clemm, and her doctor’s orders to get as much fresh air possible to battle her tuberculosis, that forced the poet to move his family (including Virginia’s mother, Maria) into a small cottage in the central Bronx. Poe’s nomadic lifestyle led him to bars and salons in Boston, Baltimore, and New York while crafting some of his finest work. But it was in Manhattan, among his network of literary contemporaries, where Poe felt most comfortable. Oftentimes, Poe would walk the full length of Highbridge in solitude and cross down into Manhattan for the thrill of the city that never sleeps. One can only speculate about the poems, prose, and verse that took shape in Poe’s mind during these therapeutic strolls.

Poe lived a half mile from Fordham University when it was still known as St. John’s College, a school dedicated to Catholic education and founded by Archbishop John Hughes of New York. It was here that Poe would often visit the school’s brothers and discuss the current events of the day while playing hands of cards. To say that a writer’s natural environment doesn’t affect their writing in some form or another is to never have written. The flora, fauna, and people that make up our communities seep into our thoughts and subconsciously form the content that is expressed on paper and across screens. One must assume that Poe was influenced by Fordham University’s clanging bells as he was out on one of his many walks or in the brothers’ company. In Poe’s short poem “The Bells” the poet writes:

What a gush of euphony voluminously wells!

How it swells!

How it dwells

On the Future! how it tells

Of the rapture that impels

To the swinging and the ringing

Of the bells, bells, bells,

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells—

To the rhyming and the chiming of the bells!

Before multi-story buildings and overdevelopment spread across the Bronx, the Long Island Sound’s majestic waters were visible in the east from homes in Fordham and Kingsbridge Heights. Poe writes about chilling winds and a nearby sea in his poem “Annabel Lee”:

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her highborn kinsmen came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

It would be daft to discount the intentionally poignant language expressed in Poe’s work while reflecting on Virginia’s inevitable death. Poe must have been extremely in tune with his natural surroundings and the man made constructs, such as Fordham’s bells, that served as constant interlocutors while he worked at his craft. Poe might have experienced a sense of cathartic liberation as he wrote in the Bronx’s vast green openness.

During the early 1900s New Yorkers zeroed in on Poe Cottage’s historical importance and preservation. Reputable public figures and elected officials such as President Theodore Roosevelt and writer Rudyard Kipling fought to ensure that Poe’s legacy would remain intact by preserving the cottage and moving it from its original location, further east on Kingsbridge Road, to where it stands today at Poe Park. However, Poe Cottage wouldn’t become a historic landmark until 1966, when the New York State Landmarks Preservation Commission deemed it so.

Poe Cottage can be found on the corner of East Kingsbridge Road and Grand Concourse and visitors may tour the cottage and observe what Poe’s household might have looked like during his time in the Bronx. The Cottage is managed by the Bronx County Historical Society and a fee of $5 per person and $3 per student, child, or senior citizen is all it’ll cost you to experience this Bronx treasure. Additionally, visitors may stop by Poe Park’s Visitor Center and participate in one of the Center’s free public programs.

Edgar Allan Poe suffered greatly during his time in the Bronx but he must have also been inspired to write and continue honing his art form while enjoying our borough’s natural beauty. “Annabel Lee” and “The Bells” are testaments to this.

In 1847, two years after Virginia’s death, Poe died in a delirious state while living in Baltimore. Many Poe biographers and historians dispute what caused Poe’s death, but what is certainly undisputable is the legacy he left behind and the voluminous catalogue of poems and stories that still resonate with readers today. One can only hope that Virginia and Poe are reunited in their kingdom by the sea.

David Cone's Perfect Game

Written by Herbert Norat / Illustration by Kayla Smith

“That would be the coincidence of coincidences, if he pitched a perfect game on Yogi Berra Day.”

On July 18, 1999 my father decided to take my brother and I to Yankee Stadium to catch a ball game. Dad always thoughtfully did this sort of thing to break up the monotony of a long work week, which was usually met by our brattish reluctance to do something exciting outdoors as we preferred to stay home, eat Chinese food and play Crash Bandicoot. Dad knew we could never say no to a Yankee game. The day was humid and in the eighties, normal weather for July baseball in the Bronx. My brother, Warren, and I had no idea that we were about to witness a nearly impossible athletic feat to achieve in professional baseball, let alone sports in general.

In 1999 David Cone had already amassed championship rings, all-star selections, broken records, and made millions of dollars as a Major League Baseball pitcher. But, at the age of 36, Cone was on the back end of his career, heading towards the inevitable finality of retirement. Yet the seasoned veteran was a trusted staple of the New York Yankees pitching rotation during their 1990s championship reign. Cone had won twenty games in 1998 and maintained a 3.55 ERA, not too shabby for a man in his mid-thirties - he was in the midst of a miraculous resurgence that very few athletes experience. Throughout most athletic careers, especially in baseball, players make their way up the amateur ranks or “farm” leagues until they are deemed worthy enough to be called up to the professional stage. If an athlete is even capable of becoming a successful player in the professional leagues then he might eventually find himself labeled a star who can consistently deliver for his team, in turn, earn great pay. But, after this stardom comes to an end, retirement is the next and final chapter that all athletes must face. Unless an athlete is fortunate enough to find himself in a “renascence” phase as David Cone did, life as a veteran athlete and journeyman is usually spent on the bench.

The summer of 1999, a simpler time before the emergence of stringent airport scanners and extreme security measures; before the mighty Twin Towers were toppled, the country was fired up for Y2K. The nation was eager to view George Lucas’ first installment of the Star Wars prequel series, Episode 1: The Phantom Menace, and Ricky Martin’s “Livin La Vida Loca” was rocking the airwaves. Around this time, President Bill Clinton had been acquitted of impeachment charges brought against him on the floor of the United States Senate for lying under oath. And here in the Bronx, Yankee Stadium was electric as Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, and Mariano Rivera were nearly invincible as they won four championships in five years (1996 and 1998-2000).

“ My brother, Warren, and I had no idea that we were about to witness a nearly impossible athletic feat to achieve in professional baseball, let alone sports in general.”

Before Major League Baseball’s steroid scandal rocked the sports world, it was common for superstars to hit over fifty home runs per year and pitch twenty winning game seasons. But, there are some feats that are nearly unattainable in baseball, including a perfect game.

We arrived at our seats in the right field stands for the game and the stadium wasn’t full to capacity, but it wasn’t empty either, instead it was comfortable enough to take in the game and not feel cramped. It was Yogi Berra Day at Yankee Stadium, and ironically, Berra caught the opening pitch thrown by Don Larsen. Forty years earlier the same duo was on the mound and behind the plate when Larsen threw a perfect game on October 8th, 1956.

At the time the Montreal Expos were a young team maintaining an average age of twenty seven years old and a budget of merely $16 million. In the other dugout, the Yankees maintained a goliath payroll of $88 million. The Expos weren’t even sure where they would play the 2000-2001 season as the team explored options to leave Canada and move the organization to Washington D.C. The young Montreal Expos team didn’t stand a chance against the experience and savvy that Cone brought to the mound. Behind home plate, Yogi Berra’s player number 8 adorned the field above the New York Yankees logo.

The very first inning saw Cone strikeout Wilton Guerrerro on three quick pitches that set the tone for the rest of the game. Sixty eight of Cone’s eighty eight pitches would be called strikes over nine innings. Next at bat, Terry Jones connected with a solid drive to right field that was the biggest threat to Cone’s perfect game. However, Paul O’ Neill leapt into action and magically dove for the ball, resulting in an out. Had O’Neill worn his glove on the other hand he might not have been able to reach the ball. Finally, Rondell White, a fearsome hitter with tremendous power, connected on a pitch that sent the ball soaring towards left-center field, only to be caught by Ricky Ledee. Cone’s perfect game was just getting started.

The bottom of the second inning led to the bulk of the Yankees’ offense as the Bronx Bombers took advantage of the Expos’ young pitcher, Javier Vazquez. First, Chili Davis was walked leading to a monstrous homerun crushed into the right field upper deck by Ricky Ledee. Later in the inning Joe Girardi’s line drive to left center field brought in Scott Brosius’ run making the score 3-0. Finally, Yankees captain Derek Jeter homered to left field, giving the Yankees a 5-0 lead.

“The triumphant pitcher was lifted up onto his teammates’ shoulders as he raised his glove overhead in victory. What bliss! To see history in the flesh and witness it amongst family and through a child’s eyes. It was a moment that can never be replicated or forgotten by anyone in that stadium, certainly not by me”

Cone had found his rhythm striking out multiple batters when a few trickles of rain led to the sky opening up and a downpour falling upon Yankee Stadium. At only a little over a half hour and in the bottom of the 3rd inning the umpire decided to bring out the tarp and cover the field. Up in the stands the three of us observed fans heading for the exits, luckily we were covered by just enough of the right field upper deck to remain in our seats. The rain delay lasted thirty three minutes before the water subsided, a length of time that must have felt like an eternity for a surging Cone, but for our trio in right field it was part of our day’s adventure.

From the fourth inning into the 6th inning Cone maintained his consistent pitching, striking out batters and forcing gently hit pop-ups. Paul O’ Neill saw much of the fielding action as the Expos managed to send a multitude of hits towards right field. In the upper deck, Cone’s strong pitching and the 0 marking the Expos hit column began to feel more palpable and the impossible perfect game started to feel like a reality. During other games when the Yankees maintained the lead, we would normally head for the exit in the sixth inning to beat the traffic heading back home. But this time was different, Cone was on a roll.

By the top of the ninth inning the entire stadium stood and waited for the final three outs. First, catcher Chris Widger was swiftly dispatched after a strikeout. Next, Ryan McGuire took the count to two balls and two strikes before solidly hitting a pitch to Ricky Ledee in left field, who bobbled the ball before securing it for an out. Finally, Orlando Cabrera came to bat as the last Expos batter of the game. Cone pitched a ball and a strike to the young hitter before he popped out to Yankees third baseman Scott Brosius who leapt up in celebratory exaltation. Cone had done it, he pitched a perfect game! In the upper right field deck the Yankee faithful flew into a frenzy as beer and popcorn were thrown over the railings showering us like the rains of earlier in the day had. Cone and Joe Girardi embraced as the pitcher fell over onto the catcher and the rest of the New York Yankees stormed the field to celebrate. The triumphant pitcher was lifted up onto his teammates’ shoulders as he raised his glove overhead in victory. What bliss! To see history in the flesh and witness it amongst family and through a child’s eyes. It was a moment that can never be replicated or forgotten by anyone in that stadium, certainly not by me.

On that magical day in July it only took David Cone a little over an hour to dispatch twenty seven Expos hitters and achieve perfection.

Bartow-Pell Mansion: A Beauty in Pelham

Written by Maryam Mohammed / Photos by Dondre Green

Pelham Bay Park is the largest park in New York City (1). The vast 3,000-acre green land includes forests, hiking trails, and is home to a number of wildlife species ranging from harbor seals to red-tail hawks. Many may also know it for the retreat of the Orchard Beach. What most probably don’t know, however, is the historical building of the Bartow-Pell Mansion. An integral part of the Bronx’s expansive and beautiful history, it sits on the east end of the park on Shore Road, overlooking the Long Island Sound. Now a museum, the mansion welcomes visitors from around the borough and the world to visit and partake in its external and internal beauty.

It is a Grecian style stone mansion with Greek Revival interiors, refaced in 1836 when a Robert Bartow acquired the estate (2). The property where the mansion currently sits was part of a 50,000-acre land purchase between the Siwanoy Indians and Thomas Pell, a doctor from Connecticut in 1654. The land treaty was famously signed under an oak tree, coined the Treaty Oak. According to the Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum, the land was chartered by King Charles II and consigned by Pell in 1666 (3). The area includes parts of what is now Westchester.

Pell began, but unfortunately did not complete, building his home. His nephew, John Pell, would go on to complete it for him in 1670. Unfortunately, the home then burned down during the revolutionary war. By the end of the war, the property was reduced to 200-acres. The land was returned to the Pell family, after Bartow purchased the land in 1836. Bartow completed the construction of the current skeleton of the home in 1842, where he lived with his wife and children.

The estate was acquired in 1888 by New York City. Structures neighboring the mansion deteriorated, but the mansion survived. It officially became a museum, in 1946, and then became a part of the National Register of Historic Places in the 1970’s. It is an official New York City Landmark. Upon your visit, you will see a home furnished with pieces reminiscent of its history - including a 6,000-piece postcard collection by Thomas X Casey showcasing photos of the last century. Like many of the Bronx’s historical landmarks, you will be welcomed by its rich history and beauty.

The Bartow-Pell Mansion is located at 895 Shore Rd, Bronx, NY 10464. It costs $5 for adults, $3 for students and seniors, and free for children under six. For more information, please visit Bartow-Pell Mansion.

1. "Bartow-Pell Mansion." The Historic House Trust RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 July 2016.

2. "History of Historic Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum and Carriage House of the Bronx, New York." History of Historic Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum and Carriage House of the Bronx, New York. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 July 2016.

3. "History of Historic Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum and Carriage House of the Bronx, New York." History of Historic Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum and Carriage House of the Bronx, New York. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 July 2016.

The Van Cortlandt House: The Bronx’s Oldest Building

Written by Maryam Mohammed / Photos by Dondre Green

The Van Cortlandt House Museum, like many of the historical buildings in The Bronx, is a hidden gem. Its history isn’t well known to many Bronx residents, and especially not those from out of the borough. It is the Bronx’s oldest building that transformed from a residential property to a museum where anyone can visit and learn more about the Bronx’s rich history. So rich that it is not a only a New York City landmark, but a National Historical Landmark. The museum is frequented by many students and is an attraction for tourists all around the world.

The Van Cortlandt House Museum sits in the Southwestern region of Van Cortlandt Park, near the cross street of 246th and Broadway. The Georgian style house dates back to the late 1600s. It was originally built - with fieldstone and brick - by Frederick Van Cortlandt as a family home for his wife and two daughters (1). The house was built on a wheat plantation, where the current Van Cortlandt Park sits, that had been in the Van Cortlandt family since 1691. Frederick unfortunately passed in 1759 before the completion of the home. In his will, he left the property to his son, James, and gave permanent residency to his wife, Frances Jay (2). The land in which the house sits was owned by Frederick’s father, Jacobus Van Cortlandt, who was New York’s Mayor in 1791 (3). The property was home to a thriving wheat plantation that shipped products across New York State and even to the South.

The house was also instrumental during the Revolutionary War. Though the property was still under British rule, Augustus Van Cortlandt, a city clerk, hid the property’s files from The British. George Washington is said to have inhabited the house on several occasions. It is rumoured that Washington used the house as one of the headquarters for his operations during the Revolutionary War. The house was a site of a decoy where Washington’s troops staged bonfires so that they could evade British Capture (4).

The Van Cortlandt Family owned the home until 1888. The property was then purchased by the City when it purchased the entire park property. The city’s Parks Department then renovated the park, adding new trees and swamps to the area surrounding the house. In 1897, the house was acquired by National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York and was transformed into a museum. It is one of the 19 houses under the Parks and the Historical House Trust of New York City. Almost one hundred years later, the house was declared a New York City Landmark (5).

Now a museum, the Van Cortlandt house attracts historical seekers from across the globe. One of its notable attractions is the home’s interior that has preserved its original aesthetic. The house is filled with furniture and art reminiscent of the era in which the house was first built. The staircases and walls throughout the home hold the spirit of its past residents. You can feel energies of the past in the home. As an emblem of the Bronx’s history, I believe it is well deserving of it praise. I strongly suggest taking the time to visit this magnificent structure and taking in its history with your own eyes.

Find out more information on how to visit the Van Cortlandt House Museum on their website.

1. "The History of Van Cortlandt House and Museum." Van Cortlandt House Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 May 2016.

2. "The History of Van Cortlandt House and Museum." Van Cortlandt House Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 May 2016.

3. "Van Cortlandt Park." Van Cortlandt Mansion and Museum. NYC Parks Department, n.d. Web. 19 May 2016.

4. "Van Cortlandt Park." Van Cortlandt Mansion and Museum. NYC Parks Department, n.d. Web. 19 May 2016.

5. "The History of Van Cortlandt House and Museum." Van Cortlandt House Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 May 2016.

The Banknote Building: Hunts Point's New Beacon of Hope

Written by Maryam Mohammed / Photos by Dondre Green

Given its rich history, it is no surprise that the Bronx is home to many historic infrastructures. From the Kingsbridge Armory to the Andrew Freedman Home, there’s no shortage of famous buildings throughout the borough. However, many of these buildings are unknown to the borough's own residents and New Yorkers around the city in general - making them underutilized, and their beauty and importance, neglected.

I would like to think of the BankNote Building as a hidden gem. I had no knowledge of the building’s existence until I began working for a small business nonprofit in 2014. After accepting the position and getting the building’s address, an internal alarm went off. My preconceived notions of the Hunts Point area deterred me initially. The area’s well documented history of crime and prostitution, plus the distance from my Kingsbridge home, made the task of traveling to the BankNote daunting. But on my first day at work, my mind was immediately changed. I would go on to spend many days exploring the building during my tenure there and engulfing myself in its external and internal beauty.

Sitting in the Hunts Point and Longwood sections, the massive structure may seem unassuming at first glance. But a self inspired tour around the building’s campus will change your mind. The brick exterior is telling of the structure’s age as it was built in 1909 and widely known as the “penny factory” for its function. The building was part of The American Bank Note Company, who printed paper and coin money. According to the building's website, the 410,000-square-foot structure is comprised of four buildings: The North, Garrison, Barretto, and Lafayette. It’s easy to spot from the Bruckner Boulevard Expressway, and if you are on the higher points of the building then you can look down into the famous Hunts Point Markets and Rikers Island.

According to the Real Deal, after being abandoned in 1985, the building laid vacant until 2007 when Taconic Investment Partners purchased it for over $32 million dollars. The developers had several ideas for creating a loft styled space for small business owners and creatives alike and even invested $25 million dollars into the buildings developments. The impact of the recession that year stalled the developers plans and the building laid dormant once again. Taconic Investment Partners then sold the property to Perella Weinberg Partners and Washington, D.C real estate investment firm Madison Marquette for a whopping $114 million. The new owners immediately began plans to revive the space. Since its turnover, the building has been transformed to a beautiful incubator for creativity, business, and opportunity.

The Bronx Business Incubator are one of the residents of the building. They rent out space to start up businesses, nonprofits, and health agencies. Some of the incubator’s tenants include the nonprofit Start Small Think Big and businesses like Luscious Wines, and even the office of Congressman Jose E. Serrano. The building houses two public schools and is home to programs such as Sustainable South Bronx and the Knowledge House. A walk around the building, to Garrison Avenue, will bring you to The Point - which is a one stop shop for creativity and grabbing a great lunch. The Point is a nonprofit dedicated to youth development by offering art programs and employment opportunities for large community of color that surround it. There are so many opportunities that Hunts Point Residents and all Bronxites can take advantage of in the BankNote.

The revitalization of the BankNote has attracted many residents, old and new, of the Hunts Point area. The building serves as a great example of restoration in an area that so desperately needs more showcases of hope and inspiration. With a little faith and time, so many things are possible.

Visit the BankNote building at 1231 Layfayette Ave, Bronx NY.

Woodlawn Cemetery

Written by Layza Garcia / Photos by Dondre Green

If you are from the northwest of the Bronx, you might know about Woodlawn Cemetery. Not for ghosts or urban legends, but for its beautiful, delicate landscaping. The tastefully organized 400 acres cemetery is designed with a lake, hills, meadows, mature trees, streams, and curved pathways while overlooking the Bronx River.

However, you might not know the deep history behind it.

Woodlawn Cemetery was founded in 1863 and designed by James C. Sidney as a rural cemetery according to The Cultural Landscape Foundation. However, in 1867, the cemetery trustees moved toward a lawn cemetery style that could accommodate monuments and mausoleums. For those who don’t know, mausoleums are buildings for tombs. Woodlawn Cemetery historian Susan Olsen in WNYC’s “The Hidden History of NYC’s Woodlawn Cemetery,” details the rich history of these mausoleums. These architectural monuments set Woodlawn Cemetery apart from the rest.

Known in some circles as the cemetery of the “rich and famous,” New York’s wealthiest citizens built these grand mausoleums to show off their style and wealth. Notable American architects such as McKim Mead & White, Carrere & Hastings, John Russell Pope and many more showcased their artistic talent and expertise in designing the mausoleums that mirrored their clients’ Fifth Avenue mansions while they were still alive. Olsen states that there are 1,316 private mausoleums, the largest collection in the country.

The cemetery houses notable residents that include Duke Ellington, Herman Melville, Fiorello LaGuardia, Joseph Pulitzer, Madam C.J. Walker, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, Celia Cruz, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and many more. According to Lloyd Ultan and Shelley Olson’s The Bronx: The Ultimate Guide to New York City’s Beautiful Borough, the funeral and burial of Admiral David Farragut in 1870 put “Woodlawn on the map” as Farragut was a personal friend of General, then president of the United States Ulysses S. Grant. Because of the number of participants that marched behind Farragut’s hearse which as the president, vice president, and every member of the cabinet, no one has ever received such an honor. In 2013, Farragut’s grave and monument was named a National Historical Landmark.

In 2011, Woodlawn Cemetery was declared a National Historic Landmark. Today, there are over 300,000 people buried at Woodlawn Cemetery.

The Woodlawn Cemetery is located on 233rd street and Webster Avenue with another entrance on Jerome Avenue near the north end of Bainbridge Avenue. It is open to the public every day from 8:30am to 5:00pm. Admission is free.

Valentine-Varian House

Written by Layza Garcia / Photos by Dondre Green

I remember a day. I can’t recall whether it was fall or spring, but I remember it was a beautiful sunny day — the perfect weather to play in. I was on a class field trip and all I kept thinking was, “When are we going to go to the park?”

I was probably in the third or fourth grade and didn’t comprehend the importance of history. Certainly not of the old house we were standing in. I wasn’t aware that it was the second oldest house in the Bronx. A house that was part of one of the greatest wars in American history — the Valentine-Varian House.

According to the Historic House Trust, Valentine-Varian House was built in 1758 and was the last of the farmhouses along the original Boston Post Road, now Van Courtlandt Avenue East. Isaac Valentine, a blacksmith and farmer from Yonkers, built the two-story, 18th century Georgian house out of the native stone on his land. Its prime location gave Valentine access to crop markets in New York, and with plenty of business as a blacksmith as carts and carriages constantly passed his door on their way to King’s Bridge and Manhattan.

The house faced a number of challenges due to the American Revolutionary War. According to my Bronx bible — Lloyd Ultan and Shelley Olson’s The Bronx: The Ultimate Guide to New York City’s Beautiful Borough — the house has seen some important faces during this tumultuous time. Paul Revere, engraver, early industrialist, and one of the most famous Patriot soldiers in the war, often passed by the house with letters from the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence to the Patriots in New York City. One of our founding fathers, George Washington, who was the newly appointed general in 1775, passed by the house on his way to Boston to take command of the troops besieging the British. The book also explains that the house was taken over in the Fall of 1776 by the British Army, German Hessian mercenaries, and Tories (Americans fighting for the British). Also, the head of the French Army, Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur (or Comte de Rochambeau) and his soldiers also encamped in the farmhouse in July of 1781. The house was in the middle of six battles. And, through all of this, Valentine remained in the house.

After the war in 1789, John Adams visited the house en route to New York City to be inaugurated as the nation’s first vice president. President George Washington once again went by the house for a second time on his way to visit the New England states.

Due to the effects of the war, farmers in the area were faced with great hardships in repairing the wreckage of their homes and lands. Valentine was impoverished and in deep debt. According to the New York City Parks Department, he was forced to sell the property in 1972 to Isaac Varian, a butcher and farmer. The Varians kept the house for three generations. One of his grandsons, Isaac Leggett Varian, served as mayor of New York City from 1839 to 1841. Due to increasing urbanization, rising property values, and real estate taxes, it was no longer profitable to operate a farm in the area by 1905. The house had to be sold again and was passed through another family ownership before being donated it to the Bronx County Historical Society in 1965.

The house was then moved diagonally on Bainbridge Avenue, between Van Courtlandt Avenue East and 208th Street, from its original location. The move took two days. The house retains the original floorboards, hand-forged nails, and homemade mortar. There’s one room that displays a section of the interior wall structure protected by glass. The house operates as the Museum of Bronx History.

The Valentine-Varian House is a true window of how people lived during the colonial period. But more importantly, it is a symbol of how the Bronx played a role in one of the important wars that formed our great nation. As a Norwood resident of over 20 years, I am proud to see this house in my borough.

According to The Bronx County Historical Society, William F. Beller, an official in the New York Customs House, acquired the house in 1905 and his son William C. Beller donated it to the Bronx County Historical Society in 1965. With Beller’s financial help, the house was then moved diagonally on Bainbridge Avenue, between Van Courtlandt Avenue East and 208th Street, from its original location. The house retains the original floorboards, hand-forged nails, and homemade mortar. There’s one room that displays a section of the interior wall structure protected by glass. The house now operates as the Museum of Bronx History.

Visitors will notice a stone statue known as The Bronx River Solider, located on the north lawn. Lloyd and Olson state that after the Civil War, John Grignola was hired to carve a statue of a Civil War soldier for the Oliver Tilden Post of the Grand Army of the Republic to mark the dead that were being buried in Woodlawn Cemetery. It was rejected by the GAR post because it was marred by a chip. Grignola then gifted the statue to John B. Lazzeri, an official at Woodlawn Cemetery. In 1898, it was placed on a granite pier in the Bronx River behind his house south of Gun Hill Road. Over six decades, the L-bolts that were holding the statue in place began to loosen and the statue fell over in the Bronx River. The Bronx County Historical Society found the statue after The New York City Parks Department stored it in a warehouse. Arrangements were made to restore the statue and place it on the lawn of the Valentine-Varian House for safekeeping.

The house is a true window of how people lived during the colonial period but more importantly how the Bronx played a role in one of the important wars that formed our great nation. As a Norwood resident of over 20 years, I am proud to see this house as I walk home.

The Valentine-Varian House also known as the Museum of Bronx History is located at 3266 Bainbridge Avenue in the Bronx, NY. It costs $5 for adults, and $3 for students, children, or seniors. For more information, please visit The Bronx County Historical Society.

The Edgar Allan Poe Cottage

Written by Layza Garcia / Photos by Dondre Green

Growing up, I always wondered about the white little cottage on Kingsbridge Road. It seemed very odd to me—, almost out of place. Such a small, peaceful looking house surrounded by the loud main road, and huge buildings. “Who lives there?” I would ask my mother as we rode past it on the bus on our way to Fordham Road. It wasn’t until my freshman year in college, while taking a writing class on detective and mystery fiction, that I learned who actually lived there. It was one of America’s greatest authors and poets, Edgar Allan Poe. He had once lived in our beloved borough of—The Bronx.

For the first historical piece on Bronx Narratives, and being that we are in the month of October, it only felt right that we start off with Poe (who was otherwise known as The “Master of the Macabre”) and his stay at the cottage. The Edgar Allan Poe Cottage was built in 1812 and owned by John Valentine, according to Lloyd Ultan and Shelley Olson’s The Bronx: The Ultimate to New York City’s Beautiful Borough

The cottage originally stood on Kingsbridge Road, east of Valentine Avenue, which was formerly known as Fordham Village. Poe, along with his young, ailing wife Virginia Clemm (who was also his cousin), and mother-in-law Maria (who was also his aunt), rented the cottage for $5 rent per month or $100 per year. Ultan and Olson state that he moved his family in the summer of 1846 in the hopes that the fresh county air would improve his wife’s condition who was struggling with tuberculosis.

The two-story cottage is quite small and simple. The first floor has a sitting room, bedroom, and kitchen. The second floor has another bedroom and study room. There is no heating or bathroom. However, even with the minimal furnishings, the family loved their time there. Besides taking care of his wife, Poe wrote some of his most celebrated poems in the house — including, “Annabel Lee” and “Ulalume.” According to Jimmy Stamp’s “When Edgar Allan Poe Needed to Get Away, He Went to the Bronx,” the house most likely also inspired Poe’s final short story, “Landor’s Cottage.”

The country life was going well for Poe until January 30th, 1847, when Virginia succumbed to her illness and died in the cottage’s first floor bedroom. Poe stayed in the cottage until his mysterious death in 1849 when he left on a lecture tour to raise money. He wanted to start a new literary magazine in Baltimore, Maryland.

It is uncertain on the immediate use of the cottage once the Poe family left. However, the cottage was in complete disrepair. In 1889, William Fearing Gill bought the cottage for $775 at an auction in the first step of preservation after the Parks Department considered it too expensive to restore. In 1895, the New York Shakespeare Society purchased the cottage for use as a headquarters with the intent to maintain it in the condition which Poe used it. However, with the widening of Kingsbridge Road, they lobbied the New York Sate Legislature to relocate the house across the street and to establish a public park surrounding it (—Poe Park). It wasn’t until 1913 that the cottage was moved and opened to the public, along with the park.

In 1962, Poe’s Cottage was designated a landmark in The Bronx and in 1966 it was recognized by the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission. Then, in 1975, the Bronx County Historical Society became its permanent custodian. Some of the furnishings such as Poe’s rocking chair and the bed in which Virginia died are still in the house today (anyone want to conduct a séance?). Other items in the cottage were not used by Poe himself, but arranged by Poe’s admirers that visited his home. Whether you are a Poe enthusiast or history buff, the cottage serves as a historical glimpse of The Bronx’s rural past and an intimate portrait of the life of one of America's most famous writers.

Edgar Allan Poe Cottage is located at Kingsbridge Road and the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, NY.

It costs $5 for adults, and $3 for students or seniors.

For more information, please visit The Bronx County Historical Society.